Barking mad No.10 has, as anticipated, shifted its sights and focussed eyes on the BBC this past weekend, in a story headlined by The Times (which is also conincidentally angling to put out a Radio 4 rival) today.

No surprises really. The present Tory Government run by chief adviser Dominic Cummings was always going to go for the public service broadcaster.

There’s talk of binning the Licence Fee. Pitching the BBC as a subscription service against the likes of Netflix and Amazon. Gammons are as I write no doubt lining up to sell tickets for a once in a lifetime opportunity to witness the downfall of their second most-hated institution.

For those who don’t recall or don’t already know, I used to work there.

And I always wanted to work there too. I deployed untold amounts of energy securing just an interview. Even applied for two jobs at the same time. The recruitment process was frustrating. Weighted against me at times it seemed.

So I ended up making videos about it. Because, just like anyone like me will testify: say no to me and I’ll come back fighting louder than ever. I am that kind of pain in the arse.

Leaving the BBC back in 2017 prompted me to confront the impact working for a large-scale organisation had on me personally.

In short: I spent years believing I was hopeless at what I did. Only when I left did I finally come to understand that I was doing the very best I could and that on balance I’d pretty much done OK.

I’m critical of some of its output and fiercly defend my ‘right’ to do so.

Last year’s Proms content wasn’t especially awe-inspiring (in contrast to some over the past fifteen years). And whilst sundry other classical music commentators will point to the BBC Proms and the BBC orchestras and Radio 3 as evidence of the vital contribution the Corporation makes to the cultural landscape of the UK (and it does) and think that’s where the discussion ends, we have to be careful in remembering the difference between something not being good, and something being open to criticism purely because of the way it is funded. That’s the pay off for a publically funded broadcaster and all of its creative endeavours. And I’d rather have it, than not.

That’s why, even though I left there (and remain still) bitter that I never secured that job at Radio 3 I’d always longed for (not even the digital job back in early 2012, secured by the bloke who told me that Benjamin Britten wrote a ‘Summer Symphony’), I recognise the difference between me being a bitter old queen (and that being irrelevant) and being able to critique its output and that being important in itself.

The BBC is the broadcasting equivalent of an errant partner – the one who messes up from time to time, but who you go back to not because of coercive control but because of love.

And to ditch it’s present funding model (now) in favour of subscription would undoubtedly mean a great many friends, associates, and mildly agreeable individuals losing their jobs. I can’t sanction that. So I’ll fight for it instead.

That’s not to say that subscription will never be introduced. It’s possible to see the lining up of BBC Sounds (for radio) and iPlayer (for TV) as ways of separating out the BBC’s on-demand offer and preparing consumers for the possibility that they pay for the privilege to listen or watch whenever they like, but listen ‘live’ for free. It’s my view that’s the long range strategy of Director of Radio (and once touted for ‘DG Greatness’) James Purnell. That was certainly the talk of one of his ‘Get To Know Me’ sessions back in 2013 I attended.

It’s not a bad idea. Pragmatic in a way. Though quite how that would leave the great many performing groups and the musicians that form them I’m not entirely sure. And from the classical music world’s perspective, that is perhaps the plan that needs to be articulated most urgently. If the BBC’s plan is to go to a subscription model, what’s their plan for the orchestras?

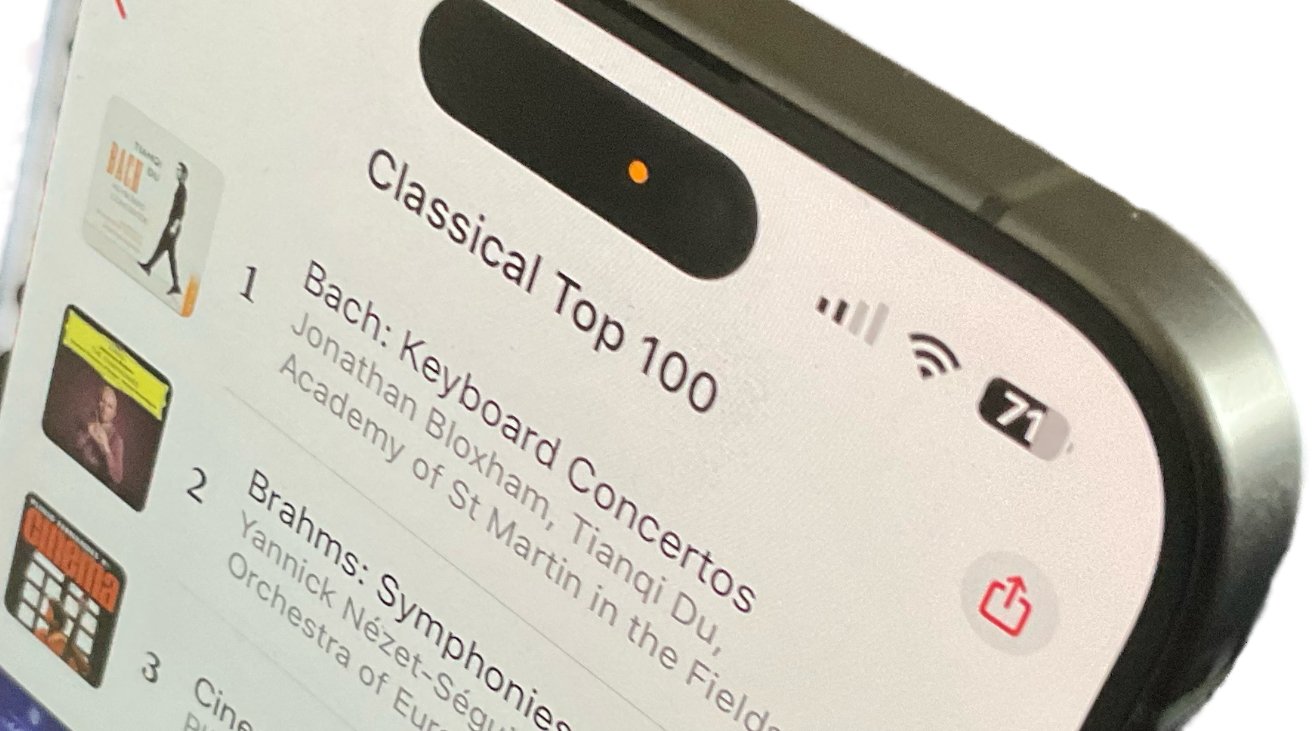

Not everyone will care, of course. We’re such a small concern us classical music lovers.

But what’s the plan?