I watched BBC Parliament Live today. I haven’t watched BBC Parliament since Brexit late-2019.

At one point the Leader of the Commons in his baggy double-breasted suit stood up to respond to Peter Bone’s (remember him?) nauseating platitudes about ‘English cricket’. If ever there was indisputable evidence of a gleeful sense of privilege and self-entitlement here it was.

Later, Rees-Mogg responded to a Conservative and then Labour MP about a call for a debate about how best to support the arts during the easing of lockdown. Twice came the response: “The Secretary of State is aware of the problems some areas of the economy are suffering.”

That’s all the arts gets in response to its present situation.

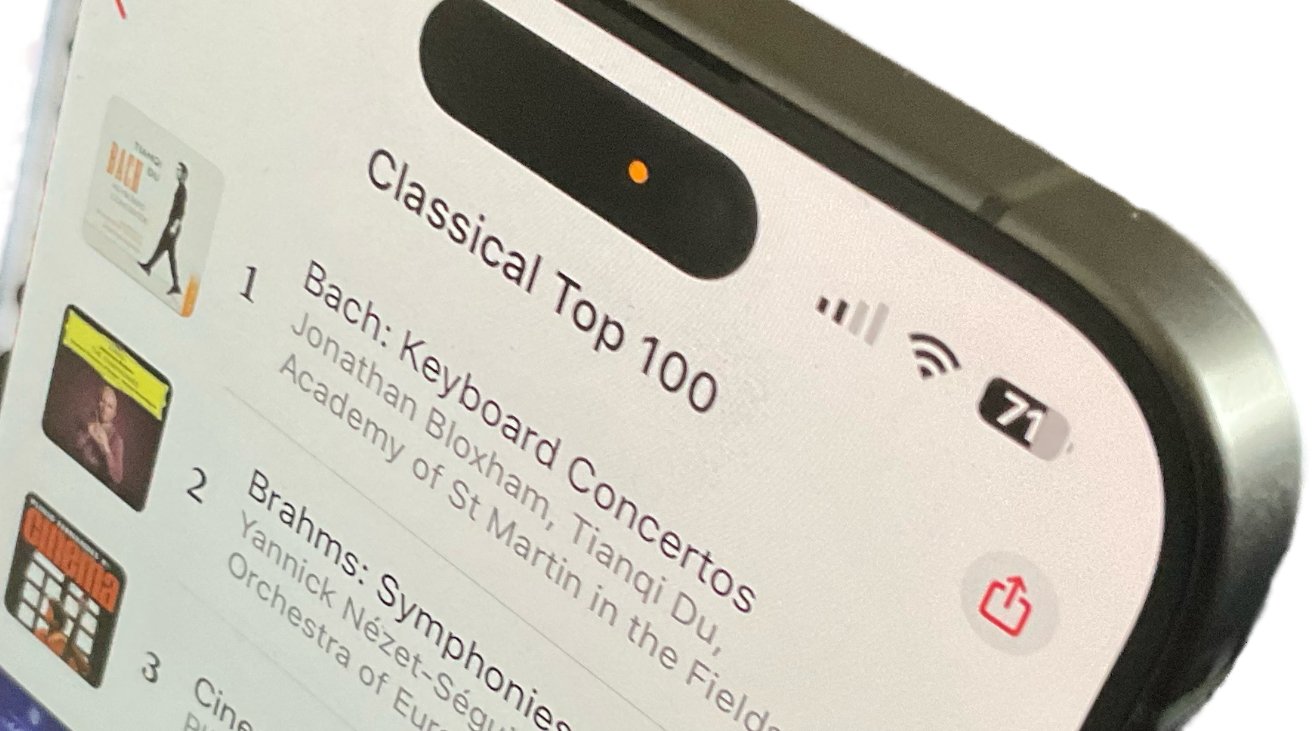

Elsewhere this week I’ve been reminded of the spectacular inverse snobbery that exists in the classical music world. For those keen to introduce the classical music canon to those who assume its not for them, there persists a view that being an advocate who knows anything about the classical music world is in itself A Bad Thing. Yes, there are those who believe that the problem with classical music is those who love classical music.

Imagine it for a moment. You’re someone who loves the thing you advocate. But there are those on one side who judge you for not knowing enough (because you didn’t go to Cambridge or Oxford), and even more unaware individuals who judge you even more harshly for following your passion and sating your appetite in a particular chosen field. Self-knowledge and first-person advocacy is an even worse educational crime it seems.

Imagine transposing that situation onto a film buff. No one unsure what film to watch at the cinema would actively criticise a film fan en-route to purchasing their ticket for knowing ‘too much’ about the medium they’re passionate about. You’d have to be a complete arsehole to dismiss anyone who knew less than you standing in the same queue. Why is there significantly less snobbery about film, but so much persistent snobbery about classical music? And is that inverse snobbery classical music (and possibly the wider-arts) biggest problem? And if it is, when did that start?

And given the situation I observed this afternoon as I glared at Jacob Rees-Mogg postulating about the joys of cricket and goading his opponents over which county will win when the game does start up again, why is this ignorance so pervasive when so many musicians livelihoods are under threat? Shouldn’t even the most ignorant and inarticulate have worked out by now that regardless of what music you play, the fact that you play music for money means its the economy you exist in that is worth supporting?

It seems not.

I am rudderless. Disconnected. Unrepresented in the present climate. And the focus of my attention seems still focussed on Westminster.

Earlier this week I trialled a coaching workshop – a session to help managers and those they interact with communicate more effectively face-to-face. I worked with a musician friend of mine to introduce the basics of coaching to friends and associates.

It was a collaborative experience. It was also dynamic in that I was responding to what was going on in the group (hence why often the best thing for a plan is for the plan to be left to one side). At its simplest level it was a teaching experience – an opportunity to share skills which I often take for granted. Skills which at the same time also have provided me with life-changing experiences. I was reminded at the end of it that I’d wanted to be a teacher.

I’ve written about why I wanted to be a teacher and why it didn’t happen in longer form in a previous post. For those that haven’t read that, it’s the pervasive thoughts about Westminster which are probably most relevant here.

A few weeks ago a colleague offered to facilitate an introduction to the Secretary of State for Education Gavin Williamson (this after I had explained to the colleague, and on a blog post, how a Department for Education wonk back in 1994 had judged me unfit to teach children on account of being a perceived ‘threat’). I thanked the colleague for the consideration and the kind offer, later concluding to myself that Williamson’s politics made it unlikely I could even respond to an email from the man let alone expect a favourable review of my case.

The Wonk’s decision-making back in 1994 aligned with Jacob Rees-Mogg’s disdainful response to reqeusts for arts support meld into one ball of unmanageable vileness that I’m now, metaphorically speaking, throwing in the direction of Oliver Dowden, the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. I can’t and won’t blame him for everything. I’m not a complete arsehole. He’s, like Rupert Christiansen rather clumsily suggested earlier today, basically a good man.

But why do the things we cherish, the things we strive for, the things that make sense for all – why do they get trampled on so brutally?

What I conclude the day thinking as I try to wrestle with all of these seemingly disparate thoughts, is this.

People hate passion. They despise enthusiasm. They are threatened by it.

In the face of these seemingly intimidating traits the majority devolve personal responsibility, reaching instead for tired tropes or misformation to mask their own ignorance and insecurities. The things that bring us long-lasting meaningful pleasure – the thing we want others to experience in a similar way to us – are the very things that the majority look down their noses at because they think its more difficult to experience than it really is.

Why should I feel guilty for that?

As long as that view is prevalent there is little point in trying to get people to experience the arts or even entertain the idea of it: the people who make the decisions will trample on the very thing we hold dear.