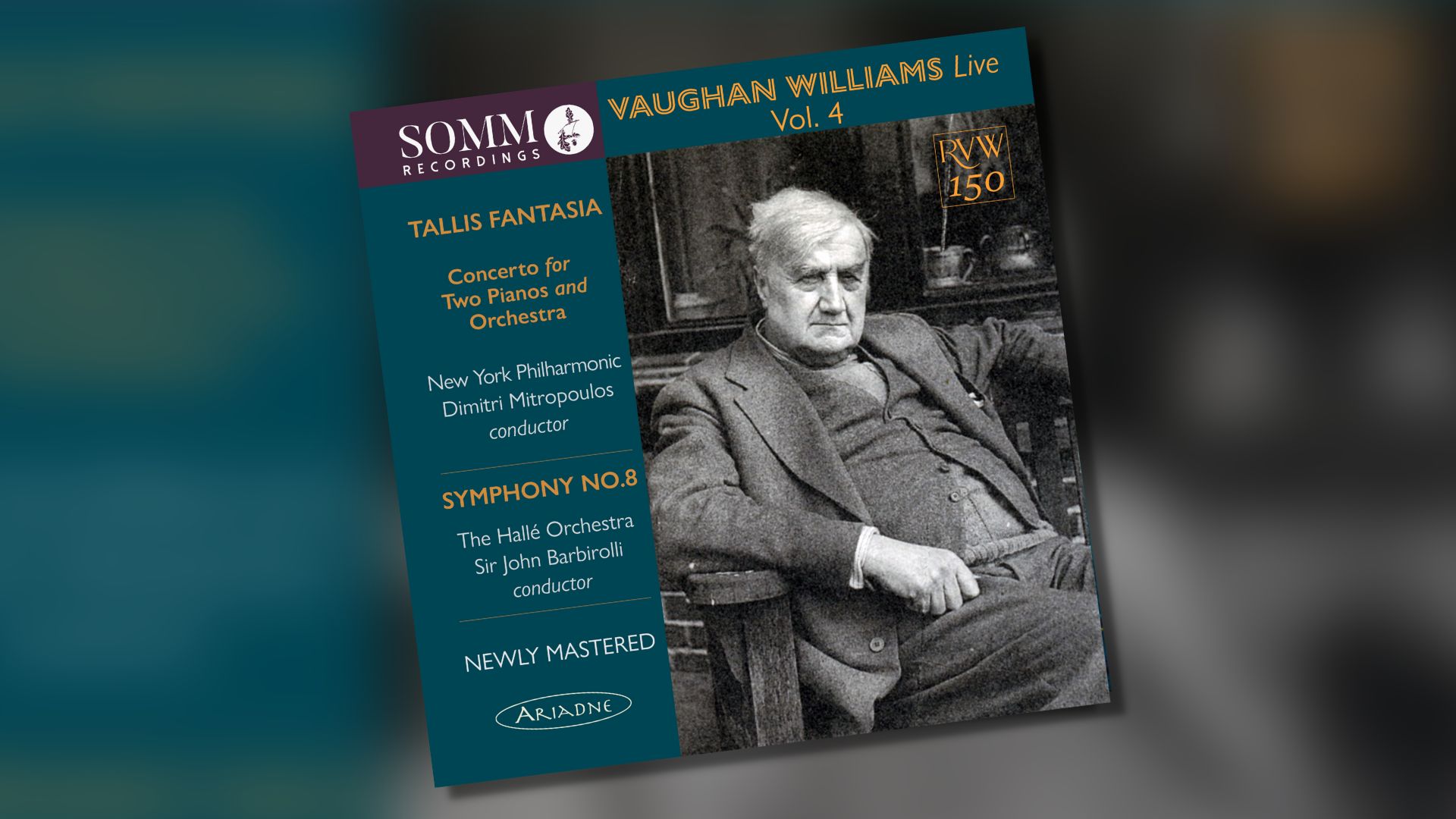

I’ve been listening to a new release from SOMM Recordings (embedded below) of music by Ralph Vaughan Williams this past weekend. I’ve come late to the record label’s Vaughan Williams celebration, joining the party at the fourth album of archive live recordings. Top line message: it’s a collection of archive delights that trigger my imagination. I love it.

This album features a US performance of a much-loved RVW classic Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis captured in 1943 when things were all smoggy and people had to bang on their TV sets to get a signal. Technically speaking there’s much about the relatively fuzzy recording the newcomer might be put off by. It’s not an ingratiating listen. There are some parts where not everyone’s playing together. It’s mono, not stereo. Mono just feels dirty to present-day ears. If you don’t already know the work this isn’t going to persuade you. Start with anything recorded in the past twenty years – like the same Orchestra’s 2014 recording.

In comparison, this 1943 US performance (where the composer was less well known) has a fragility to it that makes it painfully real, like a youth orchestra trying its very best in a concert early on in its schedule. The opening sequence of plucked strings are just about together. There are places where the bowed notes aren’t together either. This isn’t a problem. It’s a reminder that there was a time when musicians didn’t necessarily know what this music sounded like. They had nothing to go on. They were themselves playing it for the first time. In this way the mono recording (beautifully restored by Lani Spahr) captures a sense of place and moment in a way that some surgical sanitised stereo recordings don’t. As a result it’s possible that this from 1943 just has more character about it. I find it electrifying.

All of the album’s tracks challenge the implicit assumptions I hold about pieces of classical music too. Say when I read a programme note the assumption I hold is that because this work has been written about, emoted about, and its virtues extolled about, the work has always been popular. When a piece of music is written about the work it is bestowed status that perhaps it didn’t have the first time it was performed. A programme or liner note makes us assume everybody, players and audience alike, ‘got it’ from the word go, an assumption based purely on the universal appeal it has now.

But this recording is a performance that isn’t perfect and doesn’t show the work at its best. Rather it shows that it takes the enthusiasm of a conductor to get a newish work (thirty-odd years old) spotlight in a new territory. A work’s popularity isn’t guaranteed either. What did the audience in the US think in 1943? What were they saying as they left the auditorium? And what secured this piece’s future success?

These are some of the questions that arise when I listen to archive recordings. There’s a sense of place and a sense of an ‘other’ time. Inevitably I project my own preoccupations of that time onto the recording. Deep down there might even be a wish I had been present myself. Maybe listening to these kinds of recordings I’m yearning for something. Who knows. Archive triggers my imagination about the occasion I missed out on. Archive breathes new life into something you might previously overlook.

Elsewhere, I’m listening to something completely new to me. Symphony No.8. I’m listening to a mono recording of Halle’s performance from ‘64 conducted by Barbirolli. 8 years before I was born. Fifteen years before I started learning the piano as a kid. And I’m listening to this archive recording for the first time on a laptop speaker.

And boy does it sing. The material sounds modern, fresh and concise. Lots of musical and textural interest to hold my attention throughout. The entire four-movement work lasts no more than 28 minutes (making it only three minutes longer than an episode of classic Doctor Who) and yet it seems to cover more ground in terms of a story. The second movement brass and woodwind movement is a tour-de-force making all manner of demands on the players who, in this recording, deliver with precision and power. The final virtuosic final movement is a blistering listen too.

The concerto for two pianos and orchestra is another new discovery. I hear reminders of Benjamin Britten’s Piano Concerto from 30 years before. So too Poulenc’s ‘plonky’ concerto for two pianos. Its all bravado, virtuosity and in-your-face writing that I don’t quite connect with as immediately as I do with the 8th symphony. I still enjoy it. I just need to hear this unfamiliar work more to build a connection with it.

This ‘black and white’ listening experience on a laptop speaker is an introduction to a brand-new work. I check in with an artistic planner pal of mine to see whether he’s aware of it. “The eighth?” he says, “Nope. Not heard it before.” This is new territory. Something from 60 years ago connecting with me now, reminds me of yet another way it’s possible to connect with this genre of music.