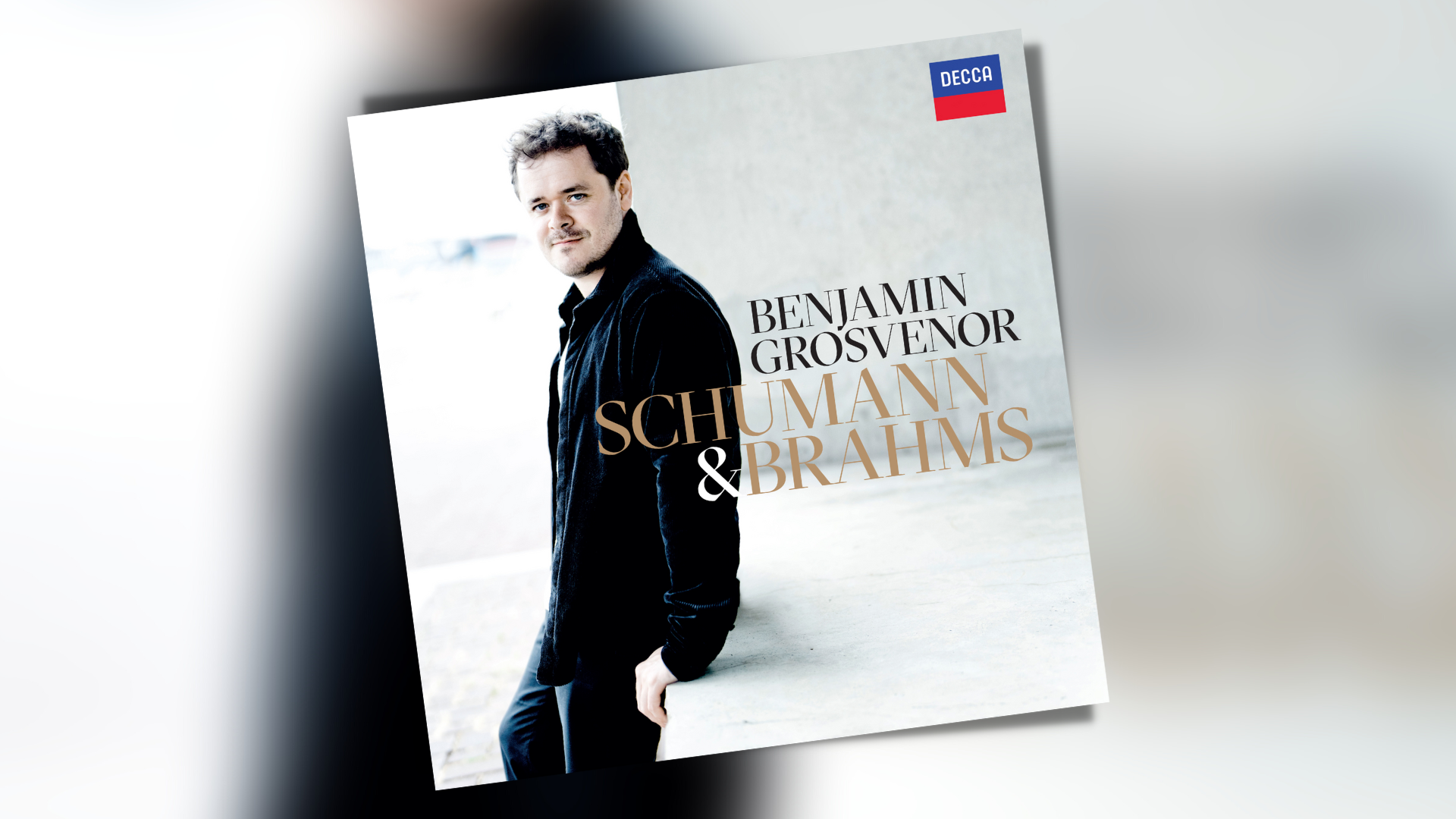

Benjamin Grosvenor’s new album out on Decca sees the pianist captivate listeners with music by Robert and Clara Schumann and Brahms. This eighth album release adds to a self-assured archive of expressive and virtuosic musical statements, some large-scale and others, like this one, more intimate but equally descriptive.

Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana is a taut piece of musical storytelling. Inspired by ETA Hoffmann’s series of stories about a fictional musician, Schumann’s set of highly descriptive movements covers a lot of ground in a surprisingly short space of time, painting a picture of a passionate, volatile, and playful individual. There are similar contrasts of mood in his Schumann’s Blumenstuck that follows, making the first forty minutes alone a gripping listen.

When Grosvenor and I speak on a Zoom call, I ask him about how the album has been put together. Clearly, I come with assumptions about how the recording industry works, assumption number one being that what we listen to on any album release is the result of some kind of compromise.

“It started with Kreisleriana,” he explains. “I’d been playing it in recitals quite a lot. It’s emotional landscape is quite turbulent. It doesn’t stay in one place for too long. It has kind of everything in it. It’s explosive at times, intimate other times. From there I wanted something that was even more heavily concentrated in its own atmosphere to go alongside.”

‘Abendlied’ from Klavierstücke fur kleine und grosse Kinder (an arrangement by Grosvenor himself) in particular is evidence of this, contrasting opening work with material that exudes an endearing sense of vulnerability.

It’s clear from our conversation that programming with emotional range in mind is vital for Grosvenor. We talk a little about how this compares to the approach he takes programming a concert. There aren’t too many differences other than having to accommodate an interval and the sometime whims or needs of a venue’s artistic director. Still, the overriding sense hearing Grosvenor talk is what we see on an album or on stage is very much driven by him. I feel reassured by that. At the same time, I’m left with how the industry doesn’t communicate this to the prospective audience: ticket buyers or listeners aren’t just buying ‘works’, they’re buying a piece of theatre manifest in the programming choices by the artist.

I first met Grosvenor at a BBC Proms launch twelve years ago. The outdoor press event saw various luminaries in attendance, of which the pianist took centre stage because of his First Night appearance. He was 18 at the time. On the opening day of the season, me and a BBC colleague recorded a behind-the-scenes ‘piece-to-camera’ serendipitously ending up on stage just as Grosvenor was rehearsing ahead of his live broadcast. Are those kind of moments nerve-wracking? Are they still?

“At first they were,” he replies. “You feel a bit exposed. The audience is there on all sides. There is something psychologically unsettling about that I think. But I feel quite comfortable there now. I’ve played there a few times now and that’s the nice thing about returning to a concert venue – the place where you’ve developed this competence on stage. Is it still nerve-wracking? It depends very much on the circumstances. But I’d say that generally speaking, much less so now than when I was a teenager.”

This for me highlights one of the negative aspects of the BBC Young Musician competition (though it says more about me than the competition I suspect). For those who have shone as a result of it, the tagline is difficult to shake. The competition projects young performers as near-adults because of their talent. When those performers become the kind of adults us middle-aged armchair musicians can relate to, the transition they’ve made seems all the more remarkable. They remain in our mind’s eye the youngsters they were when they came to our attention. Grosvenor was 11 when he won.

So, because I’m a sap for an easy question I ask him about the musical memory he recalls where he went beyond getting the notes correct to seeing an opportunity for musical expression.

He doesn’t pause to think. “I can recall that moment, actually. It was a Chopin Waltz in A Flat. I think my mother gave it to me to challenge me, to see what I could do with it. I remember I instantly connected with it. I realised this is something special. I was maybe seven years old at the time. Until that point, I’d only been playing tutor book stuff, you know, like, Stegosaurus Stomp and that kind of thing. Don’t get me wrong. Stegosaurus Stomp was great.”

Put a gun to my head and insist what it is I respond to most in Grosvenor’s playing – what makes him distinctive – is the smoothiness of his playing. The music equivalent of a silky caramel sauce complete with the occasional always-well-thought-out-and-never-over-the-top tinkering with the speed. What I can’t quite recall is whether I heard that before his Proms First Night appearance or during the season before. Regardless, it’s still evident on this album, especially in Clara Schumann’s variations based on a theme by Robert. Like Kreisleriana, the music covers a lot of ground very quickly. But in addition to the emotional range demanded of the score, Variation 4 displays that trademark Grosvenor glossy technique.

But what I come to appreciate the most about this latest Grosvenor release is the way the pianist shifts from so many different moods, conjuring up a range of colours and different characters. In this way he responds to the demands of the music fearlessly making this an album I’ve wanted to listen to repeatedly to fully appreciate Grosvenor’s ever-developing craft.