Although recollections of life as a second-year student are mostly vague, some details spring to mind. Specifically, life in the terraced house me and my friends lived in on the disappointingly unglamorous Dallas Road in Lancaster, memories of mould in my ground floor bedroom, and counting the number of slug trails found on the poorly fitting kitchen lino floor. Beyond these vague recollections, however, is something far more distinct: Sinead O’Connor’s 1992 release Am I Not Your Girl?

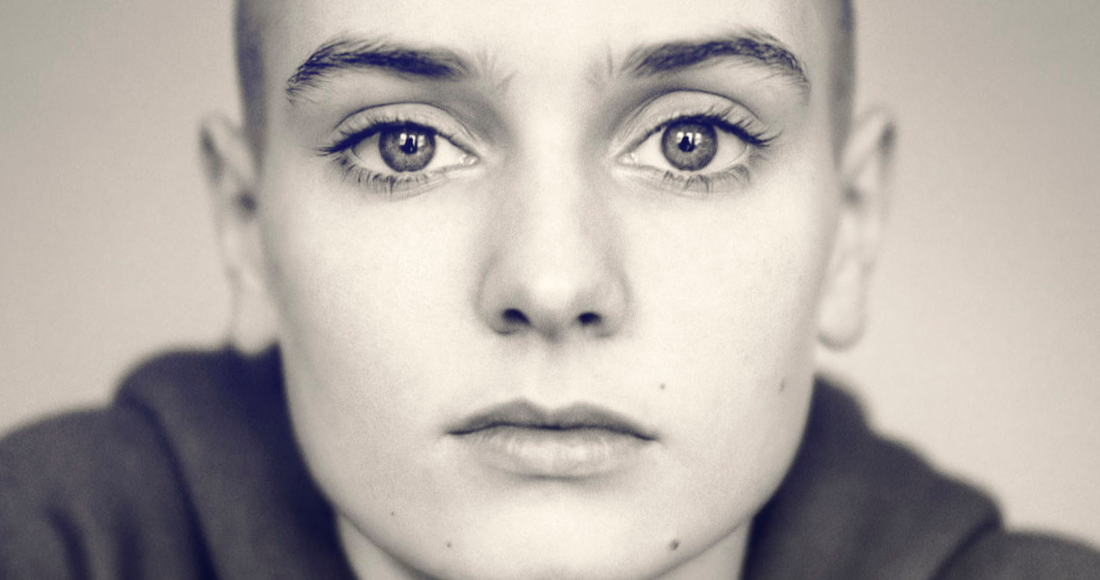

O’Connor is pictured on the front in a characteristically uncompromising defiant pose that did for the most part put me off listening to the CD when it first arrived in the post as part of that month’s Britannia Music Club compulsory purchase. I was consistently hopeless at declining the suggested recording in Britannia’s mailouts so ended up with a range of albums I wouldn’t have normally sought out at a record store, many of which went un-listened to. O’Connor’s Am I Not Your Girl? Was one such album, relegated on my bookcase unwrapped for an entire academic year before being packed up at the end of term, taken back to Suffolk and then brought back to Lancaster for my third year on campus.

My final year saw me take great strides in shaking off the boredom of my teenage years. It was on campus that I discovered Sinead O’Connor’s often overlooked big band spectacular on my new music system, a slickly designed piece of technology that seemed to transform every CD I owned into a sparkling listening experience. This transformation may well have simply been because of the additional introduction of speaker stands. In acquiring separates and speaker stands I was joining a slowly emerging throng of wannabee audiophiles, hearing music in an entirely different way – a grown-up way – fast-tracking my transition to adulthood.

After a year of ownership, listening to O’Connor’s fragile, whispering, mildly unsupported vocals set above big orchestral arrangements of musical theatre favourites an electrifying experience. At the time I was studying conducting and orchestration, an all too short module of degree studies that gave permission to revel in the joys to be found combining orchestral instruments to create spine-spine-tingling textures.

Track after track sees the microphones up close to strings, confident brass, and taut off-beat percussion tracks. These details seemed to bring the orchestral sound alive, creating a sense of party and celebration. How could anyone who scores or produces that kind of detail without revelling in that sort of detail?

Discovering Sinead O’Connor’s album at the point in time I did, coincided with new friendships at university, people who it seemed were similarly energised listening out for the tiny details that tickled frayed nerves and triggered all manner of highly-sought after pain-relieving hormones.

Why Don’t You Do Right has attitude, defiance and a delicious amount of surliness about it. I Want To Be Loved With You has sass, sauce and a sense of humour about it. A splashy middle-eight peppered with punchy chords in the brass and the saxophones that seem to staple the music to the back wall.

But the track I keep on playing time and time again with the news of the singer’s death still fresh, is Love Letters.

Springing up from a fruity bass trombone note in the introduction, O’Connor’s porcelain line hovers hesitantly above feathery strings and subdued horns that caress and soothe. Unequivocal screams of joy from the brass valiantly responded to by a beefy sax section. Who wouldn’t want to take to the stage, grab the microphone and make a good fist of the love song when you’ve got all of that at your disposal behind you?