Throughout 2022 I’m exploring my connection with the piano. I want to gain a deeper understanding of why I came to learn to play it, what the experience of playing it was back in my school days, and why I find it so difficult to return to playing it again now.

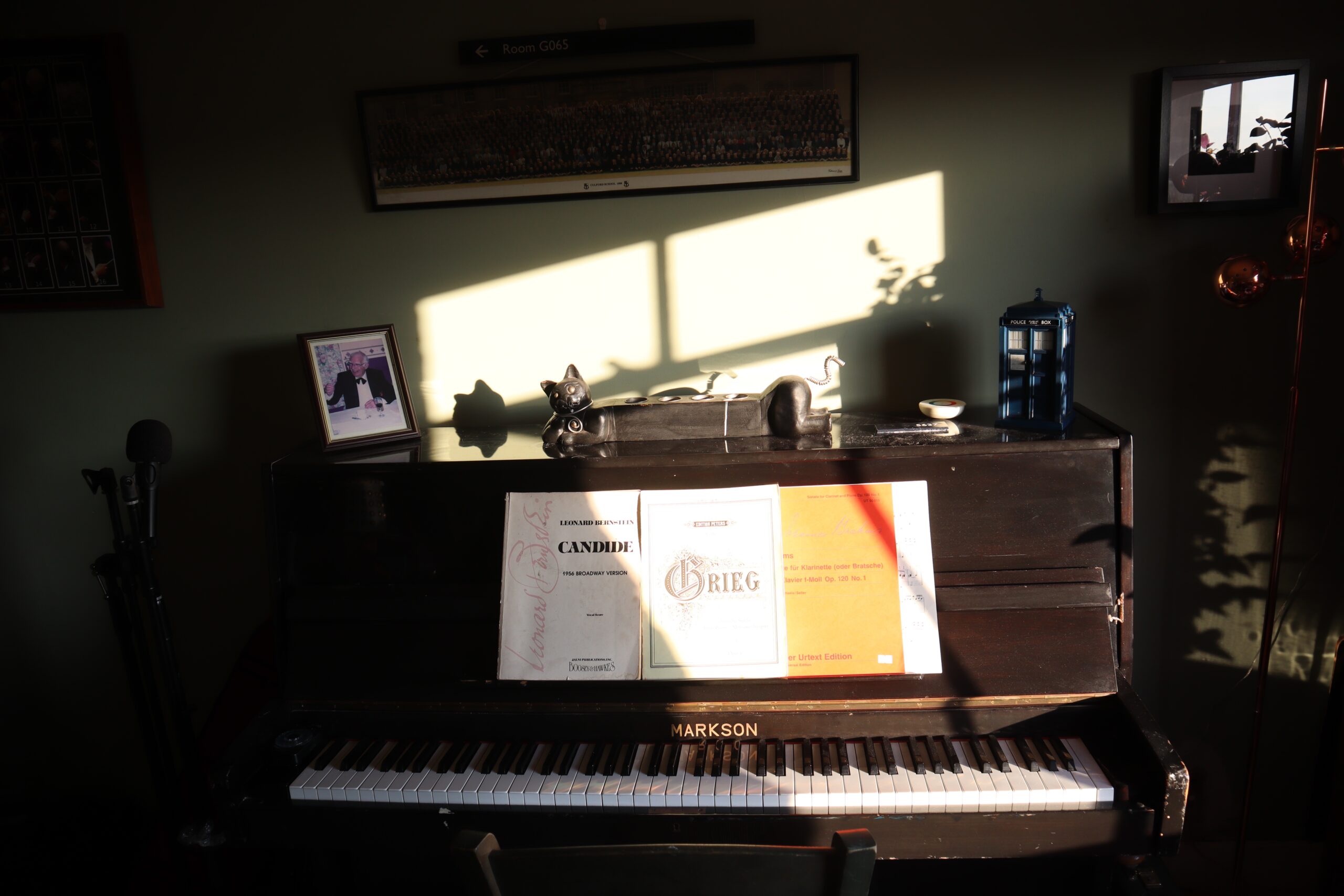

Behind me sits a black upright piano, currently dust free but not always so. The same scores sit on the music desk as a year ago. Occasionally the keyboard is approached to bash out a vaguely recalled melody, but for most of the time the piano stands silent and dejected, holding its own as impactful Zoom call backdrop.

I think we paid £750 for piano. Soon after me and my partner met and I’d moved in to his flat on King’s Avenue, we woke up one Saturday morning bleary-eyed wrapped thinking that buying a second hand piano might be a good way to start the nesting process. Later the same day at Markson Pianos showroom the trade was made, the serviced instrument delivered a few days later.

Sometimes I look at the thing and pity it. Twenty four years later it’s a piece of furniture that fills a gap but goes unplayed. Just play me. That’s why I’m here, isn’t it? That’s what other people do with their pianos, they play them. There have been occasions when I have, usually when I’m performing for others. But most times I’ll feel the weight of the past – a big hand pushing against my chest, telling me to steer clear. How can something which has in the past played such an important part in my development as a human now be such a barrier?

It got quite a lot of use to begin with, at first rehearsing a range of tenor solos preparing my still-new partner Simon for theatre auditions.

My recollection of ‘98 is one of dissatisfaction with my own technique. I was no rehearsal pianist. No pencil in my ear, a keen eye cast across the top of the instrument looking out for a two beat intro and then in on the first beat of the bar, heel pounding the floor.

I was a sluggish player, stumbling over seemingly unexpected chords. Speed changes which were at best aspirations, and dark messy key signatures promised failure, apology and shame. Mozart opera transcriptions were no good because I couldn’t expand on the simple score laid in front of me. Sondheim was too fast and too complicated. I would end up ‘marking’ bars and, after a few failed attempts quietly suggest that maybe I should just practice a little more. “It will be better when I’ve got it under my fingers.”

My main problem was not being any good at approximation at the keyboard. Plenty of others in my past had seemed adept at making a simple looking score sound considerably fuller than the manuscript indicated. Simon’s singing teacher Scilla’s ability to add a shake to any written chord gave proceedings a much grander sound. Mr Lane – my first class music teacher at Culford School – was able to make anything in The Beatles Complete sound as full and exciting as the fab four. And then there were the likes of Jerome at school or Pete at university who defied any kind of rational explanation who sat at the keyboard and did something known as ‘playing by ear’. Skills such as this made me as suspicious as I was jealous.

Forty years on I still can’t hear the title track from Ghostbusters and wince a little, remembering my peers crowding around Jerome as he bashed out Ray Parker Jr’s top ten tune with energy and attack I could only dream of.

Whilst diverting from the score seemed like cheating, there was also the need to build on the score – making more of what was printed in the manuscript. This too, like improvisation, was something completely alien to me. This was the ultimate in making yourself vulnerable to the world. This no doubt largely down to the formal tuition I received rooted in scales and arpeggios, and the value placed on accuracy, not only in practised pieces of music but also in sight-reading too. There was order in this process; chaos in improvisation.

There was too an implicit expectation established early on, originating in watching peers or teachers at the keyboard, that the really good musicians were those who played from memory or from ear. You needed to be able to improvise. You needed to be dextrous. These were the musicians who weren’t intimidated by the keyboard, they commanded it. I always felt like the keyboard insisted upon negotiation (and probably had days off at the weekend too.) the piano instead wanted to be played not participate in a scientific experiment.

How did those other musicians get to that stage? Did Jerome just wake up one morning and discover he could do this thing with this hands at a piano keyboard without so much as even one music lesson? If there were those who could sit at a keyboard and play without seemingly the many hours of practise I felt I had to put in, what was the point in continuing? Why was I wasting my time? I was going to have to run to catch up if I was able to catch up at all.