Three conductors competed in the Mahler Conducting Competition final last night at Bamberg Concert Hall in Germany. The finalists competing were Taichi Fukumura from the US, German conductor Georg Köhler, and Giuseppe Mengoli from Italy.

Mengoli secured first place and a cash prize of 30,000 Euros. Fukumura was runner-up. Georg Köhler came in third.

A record number of nineteen competitors took part in the first-round competitors took part, each rehearsing repertoire by Mahler, and Haydn with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra. Judges observing, coaxing and mentoring included conductors Barbara Hannigan, Juanjo Mena and John Storgårds, baritone Thomas Hampson and Bamberg Symphony’s Chief Conductor Jakub Hrůša.

The nineteen competitors ranged from 23 and 35 years of age, from countries across Europe, the Americas, and East Asia. Twenty-three-year-old first-round competitor Matthew Rhodes from the UK, will compete in the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition later this year with the London Symphony Orchestra at St Lukes and the Barbican, London.

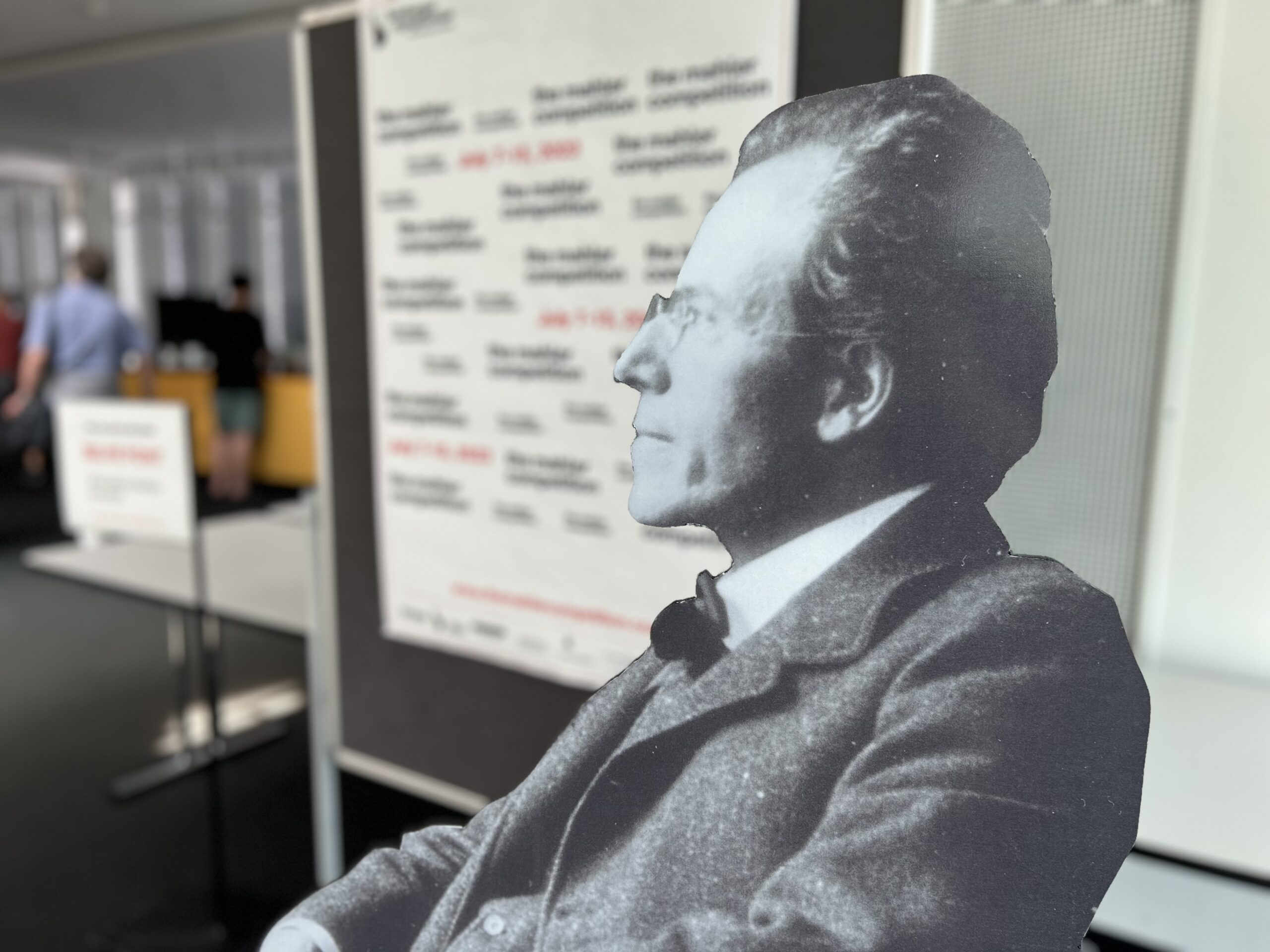

Now in its nineteenth year, the triennial competition is an important platform for conductors looking to establish an world-wide profile, bringing together those on the cusp of an international career with those at the beginning of their development showing potential. Gustavo Dudamel (who appears at Edinburgh International Festival this year) and Lahav Shani are two of the most recognisable of the Mahler’s alumni. UK conductor Finnegan Downie Dear won the previous competition in 2020. The BBC Symphony Orchestra’s current assistant conductor Dalia Stasevska made her Competition appearance in 2010.

A look of the alumni suggests that those with experience succeed at the Mahler. When Gustavo Dudamel won in 2003, he had already worked with Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. Similarly, 2013 winner Israeli conductor Lahav Shani, already working with Israel Philharmonic as an assistant conductor in 2010. The Mahler like similar conducting competitions consolidated their experience, raising their profile accordingly. Three years after his win Shani was appointed chief conductor of the Rotterdam Philharmonic; he’ll take on the role of music director at Munich Philharmonic in September 2026. Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv followed her second-place win in 2003 with a stint as assistant conductor at Bamberg Symphony from 2004, before pursuing a string of opera house contracts, landing her first chief conductorship with Graz Opera in 2016, later conducting at Bayreuth Festival in 2021.

Amongst those finalists in this year’s competition at the older end of the age range, the benefit of professional experience is evident on the podium reflected in a confident physical presence, a wide range of movement, and cogent storytelling. Bringing these skills and experience to bear results in interpretations that expose the detail in the score and, in the supportive acoustic of Bamberg Concert Hall, has the effect of leaving the audience wanting to hear more than the excerpt scheduled for rehearsal.

Georg Köhler from Germany holds the position of assistant conductor at Orchester National d’Île-de-France in addition to being the artistic director of the Chamber Orchestra of Zurich. Both are exciting musicians on the podium. Köhler was forensic in his rehearsal technique, exposing a wide range of textures and colours in the ghoulish third movement of Mahler’s seventh symphony, inspiring violins, cellos and wind with clear instructions confidently delivered, underpinned with a likable boyish enthusiasm and self-assurance.

Italian Giuseppe Mengoli, who recently concluded a two-year stint as assistant conductor at the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra and will return again with the SWR in Stuttgart later this year has been a captivating watch during the semi-finals.

Mengoli was considerably more demonstrative on the podium, utilising a variety of energetic and all-encompassing movements that commanded attention from stage and auditorium alike. And whilst the first prize could easily have been between Köhler and Mengoli, Japanese/American Taichi Fukumura was someone to keep a close eye on. His animated presence when communicating needs or wants keeps the energy high and focus sharp. It’s a refreshing leadership style that deftly subverts the expectations he established when he the wiry competitor walked briskly onto the stage like a teenager eagerly heading to double chemistry. Fukumura conducts with precision and leads with an infectious enthusiasm for his art – enacting a dancing devil caused an appreciative giggle in both the orchestra and audience today in rehearsals.

All three competitors brought about rapid transformation during their observed rehearsals. In one sequence the orchestra plays in one style, seconds later after a brief intervention from the conductor, the sound is entirely different. This is of course, to be expected. It’s just that for most of us we never get to see what happens in rehearsal, contrasting interpretations and execution in this way reveals a great deal.

There are other qualities evident across the entire competition. We are on the lookout for leadership presence, physicality, expressivity, and storytelling. We may not feel at ease with the notion, but we’re also quietly asking ourselves whether an individual is plausible or not. And if they’re not, is it simply that they’re not plausible yet? We’re listening to their style of communication – are they directing, cajoling, commanding, or appeasing? Do they look the part (whatever that means in practice). Does what they create marry up with what they’re doing on stage? Crucially, are they anticipating or following the sound? All this in thirty-minute bursts, with a camera fixed squarely on the conductor and a microphone attached to their lapel. Each under intense scrutiny in the moment but not having to show signs of how that feels.

It’s a big ask of any competitor, especially perhaps the younger ones who, whilst not necessarily in the running for the final have a big challenge demonstrating potential. Preparation is a core requirement, knowing the score inside out so that rehearsals can be executed efficiently and with impact.

Violinist and conductor John Storgårds knows all too well the importance of knowing the music inside out. “As concertmaster or leader of any kind of when there’s someone else conducting, you have to be well prepared not just for your own part but the whole work. I try to know the whole score not just my part. As a result, I expect the conductor to know at least as much about the score as I do. When some conductors showed they knew less that disturbed me. Perhaps that was also one of the reasons that made it easy for me to think ‘Okay, let’s move into conducting now.”

At the end of each competitor’s rehearsal number two violinist and jury member Mayra Budagjan canvasses opinion from the entire orchestra, relying on a network of section representatives who have collated views and thoughts on the rehearsal. Does she think that colleagues are able to determine quickly enough who feels most at ease on the platform? “Yes, very quickly, actually,” she explains, “It’s very difficult to explain, you feel it. It’s the way they use their body for conducting. Sometimes it’s the first moment, maybe after 10 seconds. You can recognize immediately who they are. Some surprise because of course, they’re very nervous. What’s important for us is that they are able to show us their emotions. Are they able to get their ideas of music out through their body even if they are scared they will get hurt?”

This is tough demanding leadership, especially for the younger candidates. Mayra details the expectations: “Once they’ve learned the music by memory and understood it, then they need to learn to conduct it. They have to work out what their vision is, and after that, they have to stand in front of the orchestra and act like a therapist. They can’t make everyone in the orchestra like them.” Communication is key. “If that communication is done wrong, then the orchestra immediately will say,” she says smiling, “‘No, thank you!’”

The artificial nature of the conducting experience necessary for judging to be done equally makes the conductor’s role a performance that is scrutinised like no other. Joining the local audience on the night of the finals will be agents, looking to see who they believe they can secure concerts for. High expectations then for all three finalists even though there are no guarantees. To supercharge their careers competitors are rightly expected to push themselves.

What challenges will this next generation of conductors face? Jury member Juanjo Mena was swift in his response when I asked, “Distractions,” he replied gloomily shaking his mobile phone in his hand. “They will be competing with mobile phones.”

John Storgårds who began his role as Chief Conductor at the BBC Philharmonic shortly before the BBC announced its intention to cut one of its performing groups plus 20% of its players from English orchestras, inevitably adopts a bleak outlook, pointing to the current lack of political advocates in classical and the wider arts. “In some respects, the challenges are the same as they have always been, by which I mean the real work of music making and working with orchestras. But nowadays, there’s the threat of people in power not having enough of knowledge, respect or understanding for how important the arts are, how important education is, how important is to be a human being.”

Turning these challenges into opportunities for those in the first, second, and third places there will be a high expectation though not perhaps any greater guarantee. When you witness human beings make themselves vulnerable for their art and their aspirations it’s not surprising you end up connecting with them even after only two short observed rehearsals. Not getting through to the final doesn’t necessarily spell the end of the road.

Watch the Mahler Competition Final on catch-up via medici.tv