In my experience, it’s the smaller scale events where there’s a greater likelihood of discovering something new. Cheltenham Music Festival is a good example, where leading artists currently on the circuit are shunning the predictable in favour of the unfamiliar or the unknown. Yay.

In this year’s eight-day festival Mark Simpson and the Doric Quartet performed music by Thomas Ades and Alban Berg, the Maxwell Quartet premiered the Cheltenham/Spitalfields co-commission by James MacMillan We Are Collective, and there was music by Webern and Schulhoff from the Leonkoro Quartet.

My hunch is that much of this is down to Head of Programming Michael Duffy (billed above Co-CEOs in the programme by the way) and the way Cheltenham’s marketing team understand exactly what the Festival’s values are. I saw the same programming characteristics in the two concerts I attended towards the end of the Festival.

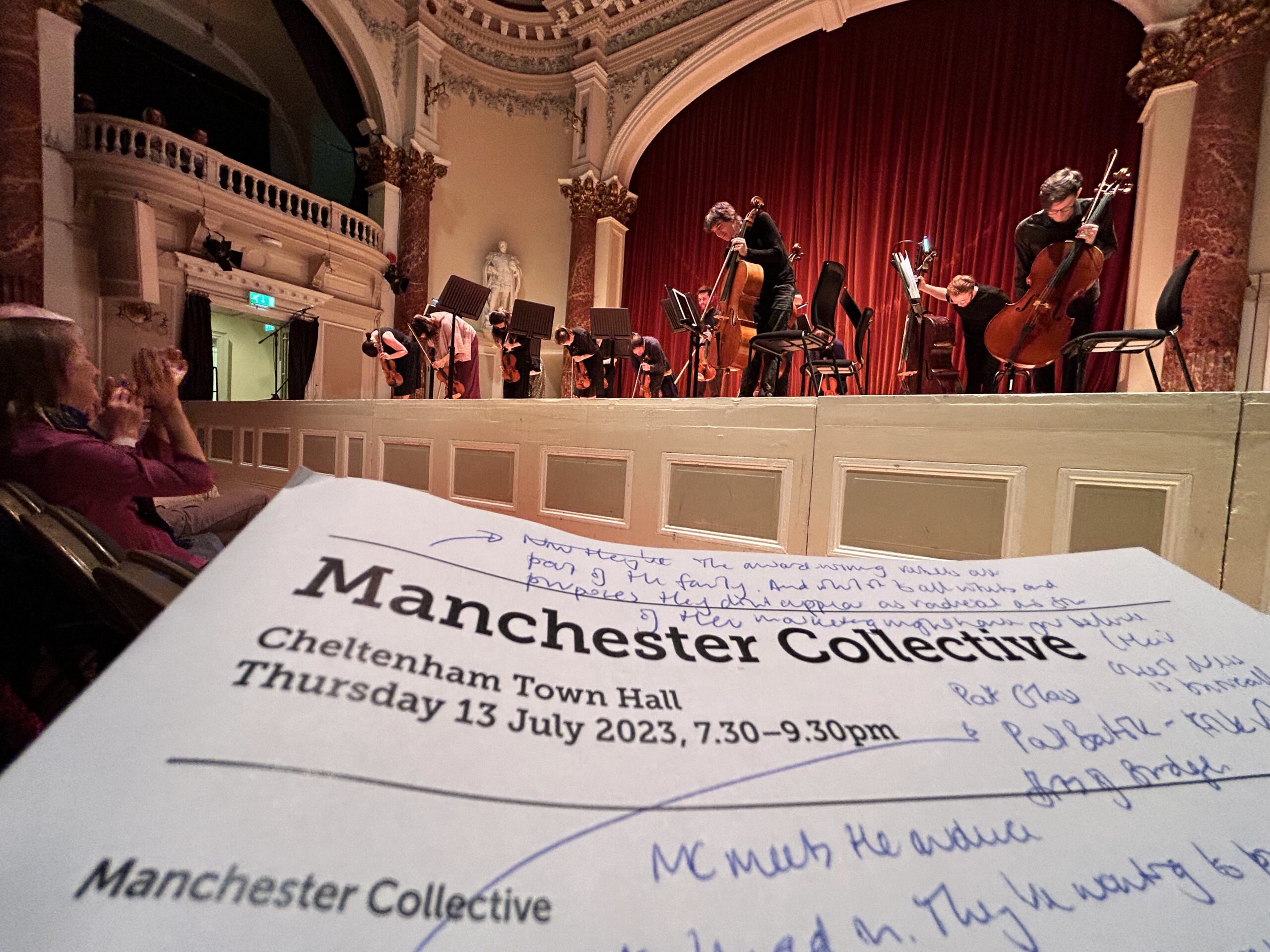

The first from award-winning Manchester Collective whose tenacity has over a seven-year period seen them build a national profile, secure a residency at the Southbank, and collect an RPS award recognising them for their achievements. Theirs is an edgy vibe that one might assume was at odds with the Gloucestershire audience who judged by external appearance might be more inclined for well-known much-loved favourites. Wrong. The bill might have presented some challenges for a Thursday night crowd, but these were deftly mitigated. Strauss Metamorphosen for string septet might not necessarily be your first choice, though Raki Singh’s unaffected introduction helped establish our connection with the human beings on stage.

At Cheltenham, Manchester Collective continue to demonstrate their characteristic versatility, remaining true to their values at the same time as understanding the crowd they’re playing to. Caroline Shaw’s response to the 75th birthday of Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks, for example – the five-movement fifteen-minute Plan & Elevation – is a satisfyingly descriptive work that is fresh and engaging, even if on paper it might potentially scare the horses. In programming this Manchester Collective show how they meet their risk-taking audience head-on. Deserved enthusiastic, delighted and surprised applause followed, particularly for their performance of Kilar’s Orawa – a toe-tapping surprise for us in the auditorium.

Similarly, Laura van der Heijden’s sensitively crafted eleven-o-clock Pittville Pump Room programme featured off-the-beaten-track-for-most composers written either at the beginning of the compositional or journey or with an eye squarely placed on the audience. Schnittke’s baroque pastiche Suite in the Old Style, packed full of delicious surprises including the ‘repeated wrong chord’ in the last movement, delighted, so too the ravishing harmonics during the tender third movement Menuett. Florence Price’s Night and Lil Boulanger’s Reflets well-chosen palette cleansers followed the exquisitely precious Roseland by Michael Zev Gordon, a Cheltenham commission from 2008, created a rewarding moment of theatre.

Both Laura and Manchester Collective are doing something different and appreciated. By taking risks programming the unfamiliar, they’re acknowledging their trust in the audience. This strategy pays dividends. That risk means I’ve heard something new. As a result, I’ve been playing Caroline Shaw’s Plan & Elevation a lot since returning from Cheltenham, so too Kilar’s Orawa from YouTube (even though it’s got a conductor, I’d recommend Jaarvi and the Baltic Youth Orchestra’s 2018 performance of the piece if you’ve not heard it). They are doing what Professor Leah Broad was advocating (broadly) in Harrogate a couple of weeks ago – by playing this music we are supporting the composer.

Now back to full operational order post-pandemic, Cheltenham’s defining characteristic is easier to determine. It wears its commitment to challenging its audience lightly. There are no airs and graces. Staff mill about talking to audience and colleagues as though we’re all in the canteen, the concert almost incidental to proceedings. In some respects, this might mean there’s a mild lack of occasion for each event, but if it pulls the punters in so be it. What’s impressive is that the audience trusts the Festival, and they’re willing and able to sign up. That’s important because it means the Festival is satisfying an audience comparatively under-served (if you look at the tribute acts and experience nights that dominate the Cheltenham Town Hall programming for example).

A special mention of a surprise discovery in the brochure and programme notes. Quietnotes brings the practice of mindfulness to music listening. It is a relief to see Quietnotes founder Will Crawford’s work front and centre in Cheltenham’s print, describing a way of listening to textures and silences, as one way of adopting a mindful listening habit. This has been part and parcel of my listening experience for years now and has, in my view helped me deepen my understanding and appreciation of all manner of works, such that I’m now at a stage where I’m prioritising new discoveries over the core repertoire.