Category: Interviews

-

Sheffield Chamber Music Festival: a jewel in Sheffield’s cultural crown

Sheffield Chamber Music Festival is a reminder of what community feels like when classical music is proudly part of the cultural offer, when musicians at the top of their game share their knowledge, experience and passions to create a programme that stretches as much as it entertains.

-

Neil Hannon introduces his new orchestral work ‘As The Sun Brightens, The Shadows Deepen’

Neil Hannon’s new work ‘As The Sun Brightens, the Shadows Deepen’ is premiered by the Ulster Orchestra on Friday 5 May 2023.

-

Joanna Forbes L’Estrange The Mountains Shall Bring Peace – a new RCSM commission for HM King Charles III Coronation

Music especially commissioned to mark the Coronation of King Charles III has been made available for choirs. The new anthem entitled The Mountains Shall Bring Peace written by Joanna Forbes L’Estrange was commissioned by the Royal School of Church Music and forms part of their singing project Sing for the King. Joanna – a former…

-

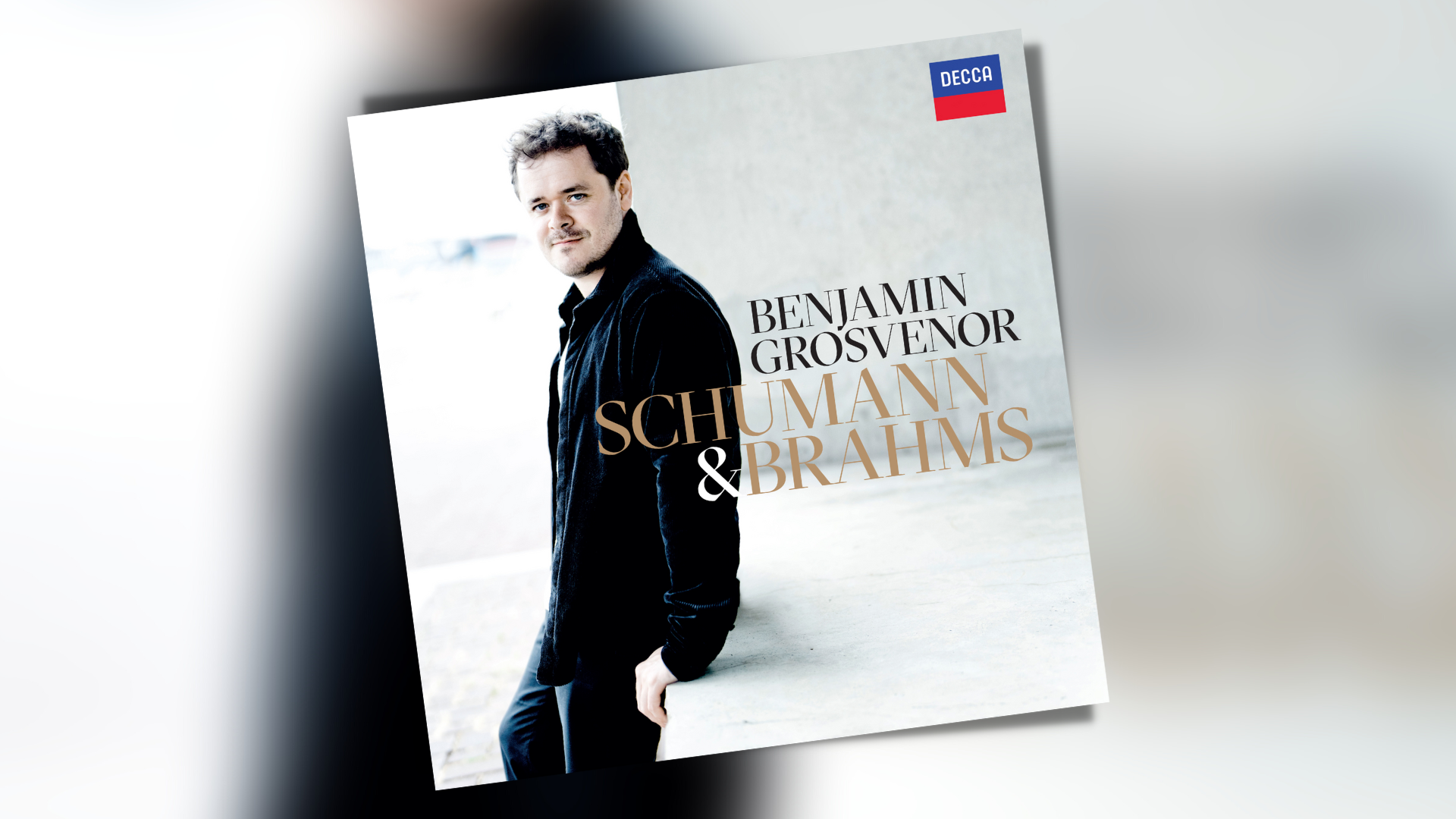

From Stegosaurus Stomp to Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana – pianist Benjamin Grosvenor reflects on his new release

Benjamin Grosvenor’s new album including Robert Schumann’s ‘Kreisleriana’ released by Decca today today, adding to the pianist’s growing archive of recordings.

-

Speaking to Gillian Moore ahead of ABO22

What a good conference and inspiring leader does, Gillian Moore brings you back to first principles.

-

Alexey Shor on writing, listening, and interviews at the International Music Festival in Dubai

Maybe our need for backstory and context is just getting in the way of what creatives want: for the music to speak for itself.

-

The curious case of composer Alexey Shor

How a former mathematician’s curiosity shines a new light on the process of composing