Tag: Beethoven

-

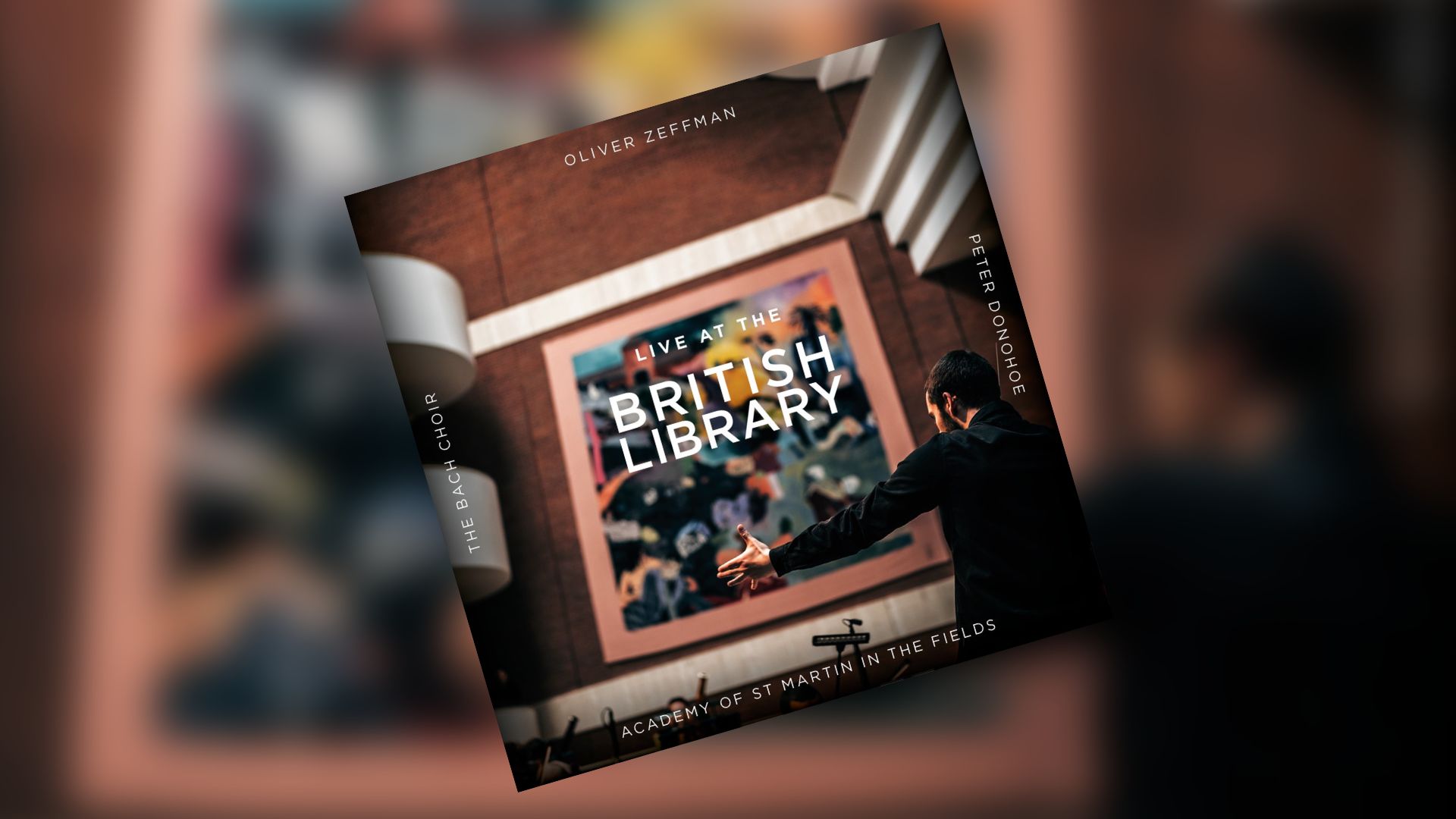

Beethoven 6 from Oliver Zeffman and Academy of St Martin in the Fields

A joyous celebration packed full of detail.

-

Aurora Orchestra play Beethoven 5 at Printworks

It’s my second time to Printworks. I’m here to see Aurora Orchestra’s Beethoven 5 theatrical ‘set piece’. I don’t necessarily feel like the target audience for this but I want to experience different formats – a useful way of seeing how the product is being packaged up for different audiences. Everything about that format is…

-

Community and connection at a Weymouth Lunchtime Chamber Concert

Human connection in a performance by a musician embarking on her career.

-

London Mozart Players, Leia Zhu, Leslie Suganandarajah and Beethoven’s Violin Concerto at QEH

Zhu is a phenomenal talent. She is reassuringly self-assured. The complete package.

-

My new pal: Beethoven’s violin concerto

Meet my new pal: Beethoven’s violin concerto. I was originally a little unsure of it when I first came across it. It wasn’t Tchaikovsky. Or Mendelssohn. Or Brahms. It seemed heavier, laden with I don’t know what. Much deference seemed to be paid to it. And it was long. Very long. Something has changed in…

-

Thoughts arising from the Oxford Philharmonic Beethoven Festival Symposium

The only way to learn stuff is to immerse yourself in it. Just don’t ask any questions. My Beethoven odyssey continues. I’ve been in Oxford today at the Beethoven Festival Symposium at the Jacqueline du Pre Music Building in St Hilda’s College. It was the first time I’ve been in amongst academics for a long…

-

Beethoven 2 & 3 from Norrington and the OAE at the QEH, and the Beach Boys

Exhilarating Norrington. Epic Beethoven. Brilliant.

-

Beethoven 5 and 7 from Andrew Manze and the NDR Philharmonie

Beethoven isn’t my go-to composer. Never has been. There’s nothing wrong per se about the man’s music. There is melody. There’s drama. In his symphonic works especially the textures in his orchestral writing are highly satisfying. The problem is (or maybe it’s not a problem) I admire the creative achievement in the same way I…