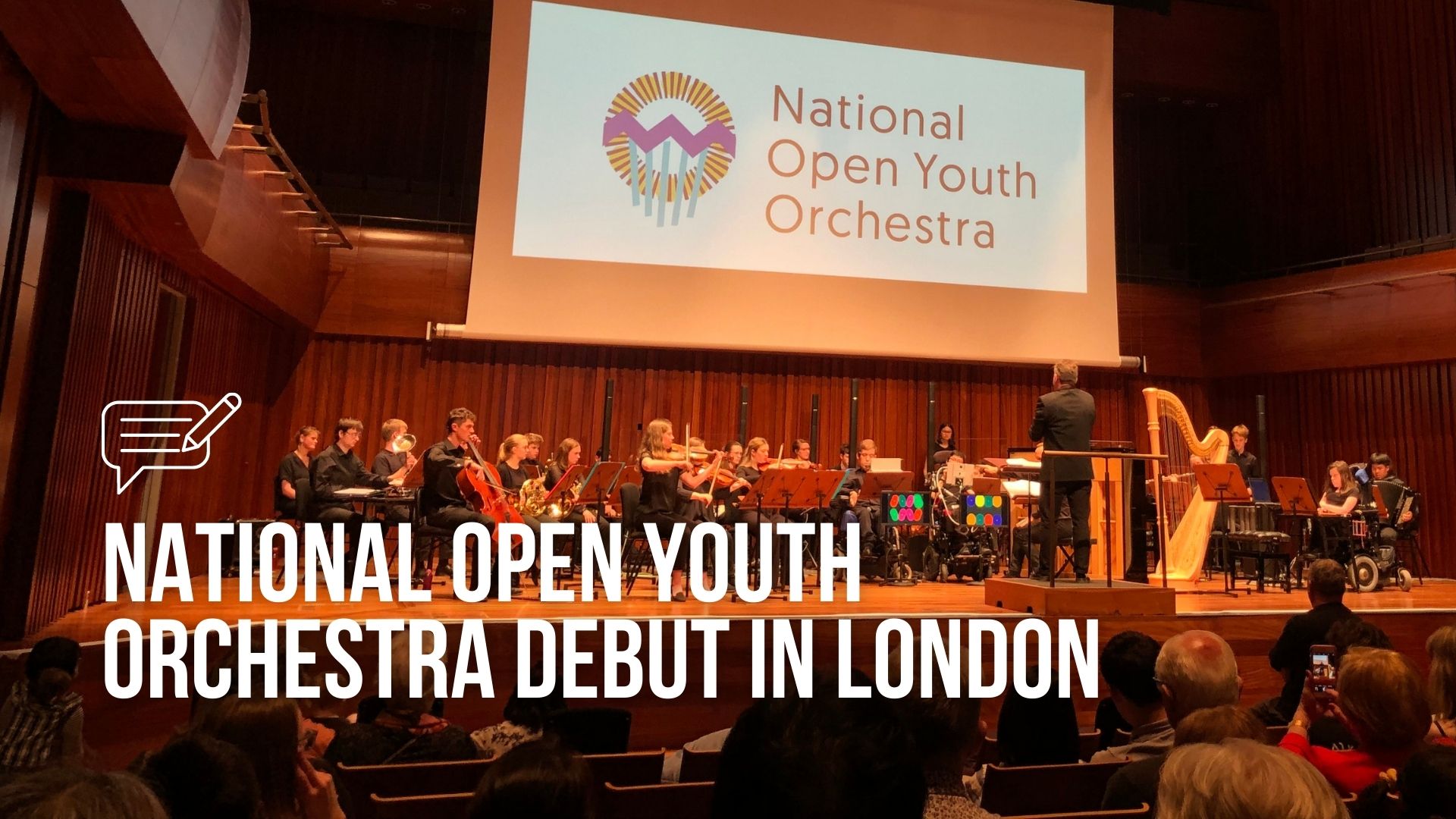

National Open Youth Orchestra’s debut concert at Milton Court in London was a life-affirming reminder of the power of music-making

The world’s first disabled-led national youth ensemble performed at Milton Court in London earlier this evening with a mixed programme of new works and arrangements including music by players in the ensemble, Hans Zimmer, Vivaldi and Alexander Campkin.

According to Scope there are 14.1 million disabled people in the UK of which 8% are young people.

Members of the 25-strong National Open Youth Orchestra (NOYO) introduced the programme from the stage including new music by harmonica and bass synthesizer player Oliver Cross, Alexander Campkin’s ‘What We Fear Then?’ – a co-commission between NOYO and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra).

The National Open Youth Orchestra was launched in 2018 intent on giving talented young disabled musicians a path into music–making. The ensemble brings together 11-25 year-old disabled and non-disabled musicians for a collaborative experience of rehearsals, performances and music creation. It’s programme of activities was severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The group’s performance at Milton Court was thought-provoking and life-affirming, a potent reminder for those of us considerably more privileged of the significant impact participatory music-making has and how often it is often taken for granted.

So much time is spent in the industry pondering how to create an appealing music entertainment experience for a younger audience – an able-bodied audience distracted by technology – whilst a significant proportion of disabled young people are excluded from even making music. Such performances as these staged to meet the needs of a neurodiverse audience, are vital for looking at music holistically rather than in terms of audience segments or ticket sales.

NOYO isn’t about just giving disabled musicians access to the stage on a Sunday afternoon. It’s about collaboration – bringing together individuals who can create music for and with one another. The rest of us look on and are reminded of why music-making is so very important a thing to advocate. In this way, NOYO is doing more than playing school-band arrangements of much-loved classics (it’s purposefully not doing that). It’s drawing on the talents of the ensemble’s members to create music for them (as opposed to for the audience).

Oliver Cross’s ‘Barriers’ was an articulation of the NOYO’s principles. Cross spoke of the impact the pandemic had on the disabled people and specifically the loss of composers Lucy Hale and Lyn Levett, after which we heard his work played by those who get all the benefits of participatory music-making by virtue of his own creative skills. Barriers displayed the musical influences of both Glass and Satie; the duet between horn (Georgina Spray) and harp (Holli Pandit) in its second movement was devastating. Shout out to the marvellous Oscar Abbot on vibes too.

In Alexander Campkin’s ‘What Fear We Then?’ there was in the complex rhythmically driven music a reassuring sense of determination that drew on Steve Reich and maybe even a little bit of Anna Meredith. There was grit and urgency here. A rare kind of joyous celebration often absent from the concert hall space.

That the NOYO is the world’s first disabled-led youth ensemble is of course wonderful. There’s also a whiff of disappointment to be found. Why hasn’t this been done before? Why isn’t this already a thing? Why is writing about it necessary?

Baby steps first perhaps. Much of NOYO’s drive comes from the fact that the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra led the way (just in time) before the pandemic with BSO Resound – the world’s first professional disable-led orchestra who appeared at the BBC Proms in 2018. And of course, the pandemic hasn’t helped. What’s necessary now is ensuring that the momentum (and therefore the funding that makes this wonderful project happen) isn’t lost.

The NOYO’s debut performance at Milton Court is a reminder of the basics. Participatory music-making is empowering, rewarding, and aspirational. It builds community and relationships. Most importantly of all, it offers the opportunity for achievement. An opportunity to be seen and heard.