Category: Review

-

Review: Andreas Ottensamer makes UK conducting debut with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Ottensamer’s youthful presence and long frame has a whiff of Hector Berlioz about it. A demonstrative artist making his debut in challenging circumstances.

-

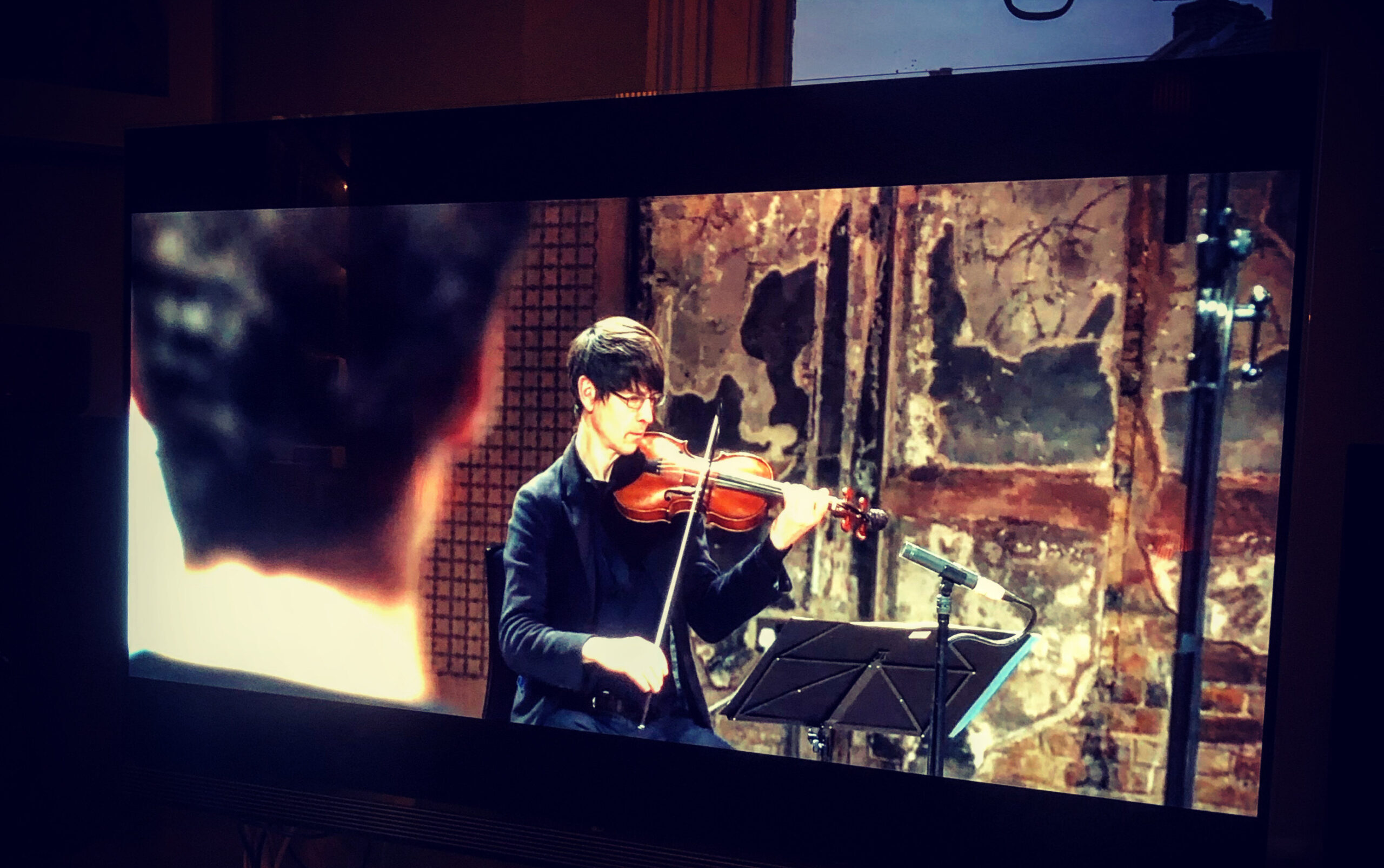

Scottish Chamber Orchestra with Nick Daniel is my new squeeze

A blissful treat that makes the idea of attending an actual concert in real life a massive ball ache.

-

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Marquee TV co-production of Bach’s St John Passion is a must-see

At best I might consider myself spiritual. But, this Easter weekend, listening to the music of Bach, I’m beginning to question. Sort of.

-

David Le Page and the Orchestra of the Swan release The Interpretation of Dreams

It’s taken a pandemic to empower a subsection of the classical music world to create the content they’ve long wanted to see on their screen.

-

Southbank Centre speaks

Musicians, play what you want. Play out of tune if you like. I don’t care This is joyous news.

-

Review: London Chamber Orchestra’s Magical Metamorphoses: Strauss, Fitkin, and Shostakovich at St John’s Smith Square

When audiences are able to step back into an auditorium, orchestras had better continue to film their concerts. I’ve got accustomed to digital streams.

-

50 Thoroughly Good bookmarked tweets from 2020

I have a habit with social media of scrolling and bookmarking. Its instinctive. There is no bookmarking strategy as such. I only really noticed I did it around February 2020. As it’s the end of the year I figured I’d take a look at the tweets I’ve bookmarked. This selection isn’t trying to be representative…

-

13 Thoroughly Good musical things from 2020

If it’s good enough for Fiona Maddocks (link at the bottom of this post) it’s good enough for this blog. I started the year wanting to explore what the music was that I connected with and, importantly, figure out why. The list that follows is a summary – the highlights – of my musical year.…

-

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra sells 16K digital tickets plus a new season for 2021

Kudos to the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra for stepping up to the plate and releasing their digital ticket sales figures for their Autumn 2020 season: a useful benchmark which can help producers get a sense of what defines success in the digital realm. The near-16,000 digital tickets sold for twelve concerts is impressive because it has…