Tag: BBC

-

The BBC Proms First Night: TV almost comes good

Even if the season-wide programme doesn’t tickle my taste buds in the way it used to ten or fifteen years ago, there are distinct improvements in the TV coverage already discernible from the First Night.

-

Advocate

Selling classical music to new audiences isn’t as difficult as you might be led to believe. Just be passionate. Sincere. Genuine. Be an advocate.

-

Suzy Klein takes on role of Head of Arts and Classical Music TV in October 2021

News arrives at Thoroughly Good of the appointment of Suzy Klein as Head of Arts and Classical Music TV at the BBC. BBC Radio 3, TV and Proms presenter Klein takes on her new role in October 2021. Thoroughly Good can’t think of anyone better to take on the role. Suzy’s path has taken in…

-

What’s the plan?

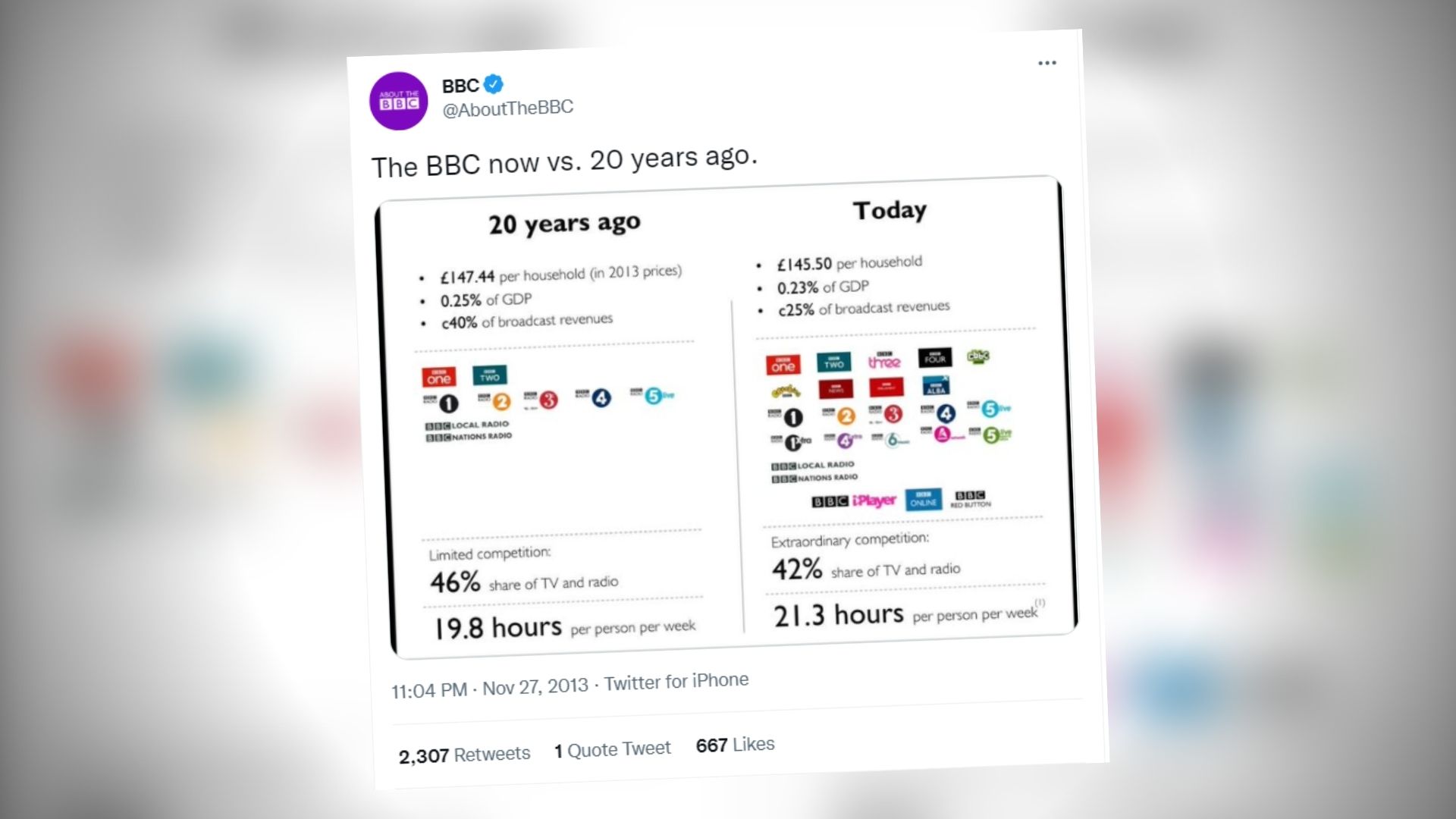

The BBC is a good thing. Let’s not fuck with it.