There are a handful of subjects that are sure to prompt me to reach for the keyboard.

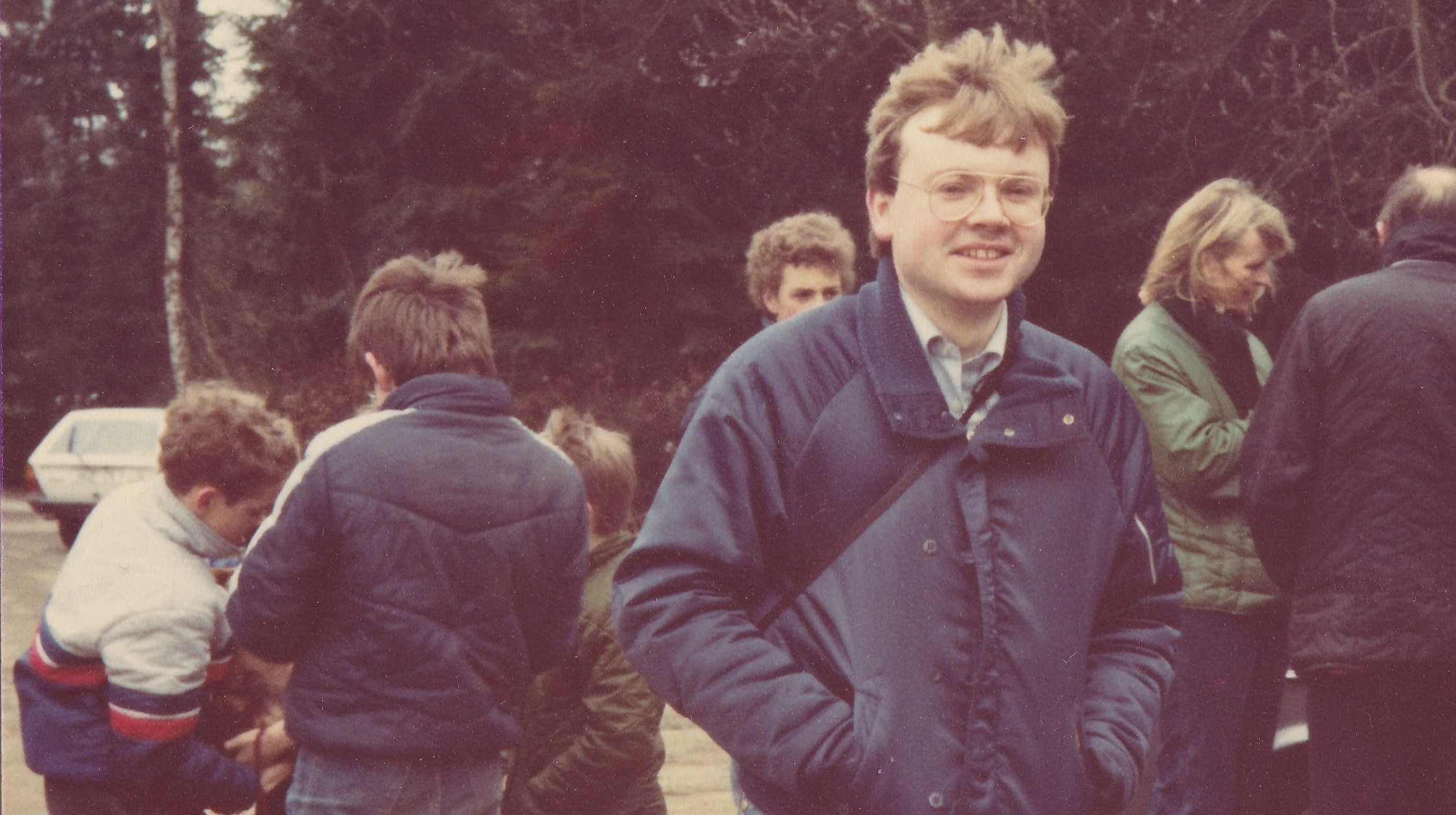

Recent examples include injustice and gratitude. Death too often triggers a similar impetus to write. Last year saw a necessary tribute to one of my school music teachers James Recknell. So too this year, with the news of the untimely and completely unexpected death of another school music teacher John Bradbury.

Unlike Mr Recknell’s tribute, this one for John feels a whole lot more difficult. I’m not entirely sure why. News of his death came in a late-night surprise phone call. “Can I call you back?” I blurted out on the phone. “I need to take 5 minutes.”

We tell ourselves stories about our past. We’re constantly reminding ourselves of those stories long after the event has passed. In some instances, the rewriting of those stories casts us further and further away from the truth. In other instances, they bring closer to the person or the idea of the person in mind.

The story I tell myself about my past may well have gone through a series of rewrites, but some characters remain consistent in each and every draft.

So it is with John Bradbury. Perhaps that’s why news of his death in his early 60s came as such a shock.

I owe a great deal to John. I see the influence he had on my motivation, determination, and attention to detail. He was disciplined. He was a poster boy for discipline. He made music something that could be excelled at, perhaps simply through a process of paying the greatest attention to the smallest detail. Repetitive relentless practise wasn’t something to be endured but embraced. By going over and over and over the same phrase, first slowly, then faster and faster, so confidence could be fostered and fluidity be more of a guarantee.

“Relax your shoulders!” he would bark as he watched me plough through whatever piece I was working on in my piano lessons. How could I possibly expect to tackle anything fast if I held tension in my arms and my upper body? And how on earth would my fingers move up and down the keyboard at speed if I let my wrists slump and didn’t ensure the movement came from my digits instead of my upper arm? He was strong on identifying faulty technique and prescribing corrective action.

The story I tell myself now of my piano lessons has one dominant image: me sat on the floor with my arms stretched above me, trying to learn a more conducive position for my wrists to optimise my playing. I passed Grade 8 as I recall. Merit, if I’m not mistaken. That’s in no small part down to John Bradbury and his relentless attention to detail.

John’s own ambition and the energy he drew upon to realise it had a critical impact on me too.

Membership of the Culford School Junior Choir was decided upon with rigour. Auditions had an other-worldly air. Membership wasn’t guaranteed; it was dependent on meeting a certain standard. The reputation of the ensemble was at stake. The Culford School Junior Choir could after all, be something to raise awareness of the school itself, hence participation in the then Sainsbury’s Choir of the Year Competition with Walter Barrie’s arrangement of Stodola Pumpa, Britten’s Old Abram Brown, and (if memory serves me correctly) Harold the Frog.

An unexpected invitation to join the school Chapel Choir came a few years later. Impressionable, spotty and and eager to demonstrate difference and (let’s face it) superiority over my peers with whom I felt I struggled to acquire credibility, the chance to go ‘on tour’ with the school Chapel Choir gave me an unexpected sense of worth.

Haydn’s Little Organ Mass sung in numerous churches across Northern Europe (so it seems to me now) when Fergal Sharkey, Aha, The Blow Monkeys and Whitney Houston featured high in the UK charts and on my Walkman made for an unlikely playlist of music that now, all these years later, still triggers a raw and unshakeable sense of self-confidence.

Later still, the Culford School Chapel Choir played a key role in Sunday services in St Edmundsbury Cathedral, the Queen Mother’s massed-choir birthday celebrations in Horseguards Parade and St Martin in the Fields. Weekly Tuesday evening rehearsals assumed a different edge: time dedicated to the necessary hard work for the forthcoming weekend’s showcase. This was a demanding process. Sometimes it felt like stupidly hard work. It pushed us. Not so much demanding as reinforcing the importance of the occasion for the choir and more so perhaps for him. The payoff? That undeniable sense of being part of a special moment.

When John left Culford School, me and Rebecca mid-way through our A-Level music studies there was an unshakeable sense that he was abandoning us for something better. He never billed it that way but the sense of loss was considerable. Such was the bond he’d created by virtue of the vision he was trying to realise.

John Bradbury had an unshakeable vision and terrifying attention to detail that was both exhausting and aspirational at the same time. To this day I still celebrate that core principle: secure solid technique and everything else will follow; strive for the very best in everything you do. To be reminded these past few days that my years with him were when he was in his first job post-studies says something about his remarkable commitment.

News of his death came as a shock. The thought of him not being around is something that will take a long time to get used to.

Unlike his boss at Culford School James Recknell, I did, during a drunken evening a few years back in central London, tell him exactly what impact he’d had on me, and I thanked him for it. Rather predictably he was uncomfortable taking the praise. No matter. At least he knew.